Identity Versus Role Confusion

ANSWER

Identity versus confusion is the fifth stage of ego according to psychologist Erik Erikson's theory of psychosocial development. This stage occurs.

Identity confusion or identity alteration involve a sense of confusion about who a person is. An example of identity confusion is when a person has trouble defining the things that interest them in life, or their political or religious or social viewpoints, or their sexual orientation, or their professional ambitions. In addition to these apparent alterations, the person may experience distortions in time, place, and situation.

From: Dissociative Identity Disorder (Multiple Personality Disorder) WebMD Medical Reference

Reviewed by Smitha Bhandari on January 22, 2020

SOURCES:

National Alliance on Mental Illness: 'Dissociative Identity Disorder.'

Mayo Clinic: 'Dissociative disorders.'

SOURCES:

National Alliance on Mental Illness: 'Dissociative Identity Disorder.'

Mayo Clinic: 'Dissociative disorders.'

NEXT QUESTION:

How can dissociated states affect daily life for someone with dissociative identity disorder?

'ALEXA, ASK WEBMD'

More Answers On Mental Health

THIS TOOL DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE. It is intended for general informational purposes only and does not address individual circumstances. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment and should not be relied on to make decisions about your health. Never ignore professional medical advice in seeking treatment because of something you have read on the WebMD Site. If you think you may have a medical emergency, immediately call your doctor or dial 911.

.Erikson's stages of psychosocial development, as articulated in the second half of the 20th century by in collaboration with, is a comprehensive theory that identifies a series of eight that a healthy developing individual should pass through from to late.Erikson's stage theory characterizes an individual advancing through the eight life stages as a function of negotiating their biological and sociocultural forces. Each stage is characterized by a psychosocial crisis of these two conflicting forces. If an individual does indeed successfully reconcile these forces (favoring the first mentioned attribute in the crisis), they emerge from the stage with the corresponding virtue. For example, if an infant enters into the toddler stage (autonomy vs. Shame and doubt) with more trust than mistrust, they carry the virtue of hope into the remaining life stages. The challenges of stages not successfully completed may be expected to return as problems in the future.

However, mastery of a stage is not required to advance to the next stage. The outcome of one stage is not permanent and can be modified by later experiences. Contents.Stages Approximate AgeVirtuesPsychosocial crisisSignificant relationshipExistential questionExamplesInfancyUnder 2 yearsHopeTrust vs.

MistrustMotherCan I trust the world?Feeding, abandonmentToddlerhood2–4 yearsWillAutonomy vs. Shame/DoubtParentsIs it okay to be me?Toilet training, clothing themselvesEarly childhood5–8 yearsPurposeInitiative vs. GuiltFamilyIs it okay for me to do, move, and act?Exploring, using tools or making artMiddle Childhood9–12 yearsCompetenceIndustry vs. InferiorityNeighbors, SchoolCan I make it in the world of people and things?School, sportsAdolescence13–19 yearsFidelityIdentity vs. Role ConfusionPeers, Role ModelWho am I? Who can I be?Early adulthood20–39 yearsLoveIntimacy vs.

IsolationFriends, PartnersCan I love?Romantic relationshipsMiddle Adulthood40–59 yearsCareGenerativity vs. StagnationHousehold, WorkmatesCan I make my life count?Work, parenthoodLate Adulthood60 and aboveWisdomEgo Integrity vs. DespairMankind, My kindIs it okay to have been me?Reflection on lifeHope: trust vs.

Mistrust (oral-sensory, infancy, under 2 years). Existential Question: Can I Trust the World?The first stage of Erik Erikson's theory centers around the infant's basic needs being met by the parents and how this interaction leads to trust or mistrust. Trust as defined by Erikson is 'an essential trustfulness of others as well as a fundamental sense of one's own trustworthiness.'

The infant depends on the parents, especially the mother, for sustenance and comfort. The child's relative understanding of world and society comes from the parents and their interaction with the child. A child's first trust is always with the parent or caregiver; whoever that might be, however, the caregiver is secondary whereas the parents are primary in the eyes of the child. If the parents expose the child to warmth, regularity, and dependable affection, the infant's view of the world will be one of trust. Should parents fail to provide a secure environment and to meet the child's basic needs; a sense of mistrust will result. Development of mistrust can lead to feelings of frustration, suspicion, withdrawal, and a lack of confidence.According to Erik Erikson, the major developmental task in infancy is to learn whether or not other people, especially primary caregivers, regularly satisfy basic needs. If caregivers are consistent sources of food, comfort, and affection, an infant learns trust — that others are dependable and reliable.

If they are neglectful, or perhaps even abusive, the infant instead learns mistrust — that the world is an undependable, unpredictable, and possibly a dangerous place. While negative, having some experience with mistrust allows the infant to gain an understanding of what constitutes dangerous situations later in life; yet being at the stage of infant or toddler, it is a good idea not to put them in prolonged situations of mistrust: the child's number one needs are to feel safe, comforted, and well cared for. Will: autonomy vs. Shame/doubt (muscular-anal, toddlerhood, 2–4 years). Existential Question: Is It Okay to Be Me?As the child gains control over eliminative functions and, they begin to explore their surroundings. Parents still provide a strong base of security from which the child can venture out to assert their will. The parents' patience and encouragement helps foster autonomy in the child.

Children at this age like to explore the world around them and they are constantly learning about their environment. Caution must be taken at this age while children may explore things that are dangerous to their health and safety.At this age children develop their first interests. For example, a child who enjoys music may like to play with the radio. Children who enjoy the outdoors may be interested in animals and plants. Highly restrictive parents, however, are more likely to instill in the child a sense of doubt, and reluctance to attempt new challenges. As they gain increased muscular coordination and mobility, toddlers become capable of satisfying some of their own needs.

They begin to feed themselves, wash and dress themselves, and use the bathroom.If caregivers encourage self-sufficient behavior, toddlers develop a sense of autonomy—a sense of being able to handle many problems on their own. But if caregivers demand too much too soon, or refuse to let children perform tasks of which they are capable, or ridicule early attempts at self-sufficiency, children may instead develop shame and doubt about their ability to handle problems.Purpose: initiative vs. Guilt (locomotor-genital, early childhood, 5–8 years). Existential Question: Is it Okay for Me to Do, Move, and Act?Initiative adds to autonomy the quality of planning, undertaking and attacking a task for the sake of just being active and on the move. The child is learning to master the world around them, learning basic skills and principles of physics.

Things fall down, not up. Round things roll. They learn how to zip and tie, count and speak with ease. At this stage, the child wants to begin and complete their own actions for a purpose. Guilt is a confusing new emotion.

They may feel guilty over things that logically should not cause guilt. They may feel guilt when this initiative does not produce desired results.The development of courage and independence are what set preschoolers, ages three to six years of age, apart from other age groups. Young children in this category face the challenge of initiative versus guilt. As described in Bee and Boyd (2004), the child during this stage faces the complexities of planning and developing a sense of judgment. During this stage, the child learns to take initiative, and prepares for leadership and goal achievement roles. Activities sought out by a child in this stage may include risk-taking behaviors, such as crossing a street alone or riding a bike without a helmet; both these examples involve self-limits.Within instances requiring initiative, the child may also develop negative behaviors.

These negative behaviors are a result of the child developing a sense of frustration for not being able to achieve a goal as planned and may engage in negative behaviors that seem aggressive, ruthless, and overly assertive to parents. Aggressive behaviors, such as throwing objects, hitting, or yelling, are examples of observable behaviors during this stage.Preschoolers are increasingly able to accomplish tasks on their own and can explore new areas. With this growing independence comes many choices about activities to be pursued.

Sometimes children take on projects they can readily accomplish, but at other times they undertake projects that are beyond their capabilities or that interfere with other people's plans and activities. If parents and preschool teachers encourage and support children's efforts, while also helping them make realistic and appropriate choices, children develop initiative—independence in planning and undertaking activities. But if, instead, adults discourage the pursuit of independent activities or dismiss them as silly and bothersome, children develop guilt about their needs and desires. Competence: industry vs. Inferiority (latency, middle childhood, 9–12 years). Existential Question: Can I Make it in the World of People and Things?The aim to bring a productive situation to completion gradually supersedes the whims and wishes of.The fundamentals of technology are developed. The failure to master trust, autonomy, and industrious skills may cause the child to doubt his or her future, leading to shame, guilt, and the experience of defeat and inferiority.The child must deal with demands to learn new skills or risk a sense of inferiority, failure, and incompetence.'

Children at this age are becoming more aware of themselves as individuals.' They work hard at 'being responsible, being good and doing it right.' They are now more reasonable to share and cooperate. Allen and Marotz (2003) also list some perceptual cognitive developmental traits specific for this age group.

Children grasp the concepts of and time in more logical, practical ways. They gain a better understanding of cause and effect, and of calendar time. At this stage, children are eager to and accomplish more complex skills: reading, writing, telling time. They also get to form, recognize cultural and individual differences and are able to manage most of their personal needs and grooming with minimal assistance. At this stage, children might express their independence by talking back and being disobedient and rebellious.Erikson viewed the years as critical for the development of.

Ideally, elementary school provides many opportunities to achieve the recognition of teachers, parents and peers by producing things—drawing pictures, solving addition problems, writing sentences, and so on. If children are encouraged to make and do things and are then praised for their accomplishments, they begin to demonstrate industry by being diligent, persevering at tasks until completed, and putting work before pleasure. If children are instead ridiculed or punished for their efforts or if they find they are incapable of meeting their teachers' and parents' expectations, they develop feelings of about their capabilities.At this age, children start recognizing their special talents and continue to discover interests as their education improves.

They may begin to choose to do moreactivities to pursue that interest, such as joining a sport if they know they have athletic ability, or joining the band if they are good at music. If not allowed to discover their own talents in their own time, they will develop a sense of lack of motivation, low self-esteem, and lethargy.

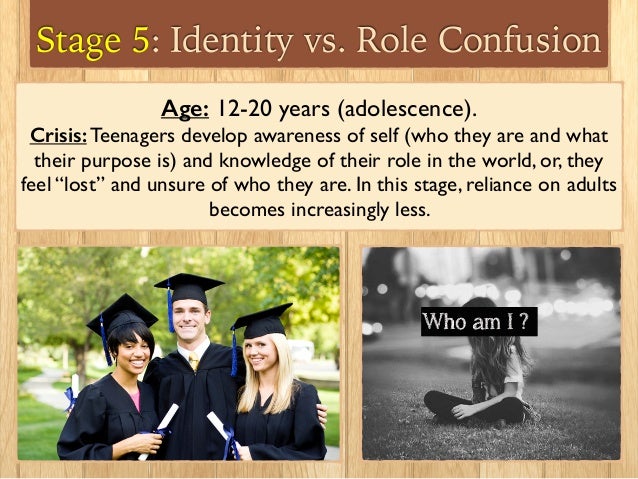

They may become 'couch potatoes' if they are not allowed to develop interests.Fidelity: identity vs. Role confusion (adolescence, 12–19 years). Existential Question: Who Am I and What Can I Be?The adolescent is newly concerned with how they appear to others. Superego identity is the accrued confidence that the outer sameness and continuity prepared in the future are matched by the sameness and continuity of one's meaning for oneself, as evidenced in the promise of a career. The ability to settle on a school or occupational identity is pleasant. In later stages of adolescence, the child develops a sense of.

As they make the transition from childhood to adulthood, adolescents ponder the roles they will play in the adult world. Initially, they are apt to experience some role confusion—mixed ideas and feelings about the specific ways in which they will fit into society—and may experiment with a variety of behaviors and activities (e.g. Tinkering with cars, baby-sitting for neighbors, affiliating with certain political or religious groups). Eventually, Erikson proposed, most adolescents achieve a sense of identity regarding who they are and where their lives are headed.The teenager must achieve identity in occupation, gender roles, politics, and, in some cultures, religion.Erikson is credited with coining the term '.: 29 Each stage that came before and that follows has its own 'crisis', but even more so now, for this marks the transition from childhood to adulthood. This passage is necessary because 'Throughout infancy and childhood, a person forms many identifications. But the need for identity in youth is not met by these.' This turning point in human development seems to be the reconciliation between 'the person one has come to be' and 'the person society expects one to become'.

This emerging sense of self will be established by 'forging' past experiences with anticipations of the future. In relation to the eight life stages as a whole, the fifth stage corresponds to the crossroads:What is unique about the stage of Identity is that it is a special sort of synthesis of earlier stages and a special sort of anticipation of later ones. Youth has a certain unique quality in a person's life; it is a bridge between childhood and adulthood.

Youth is a time of radical change—the great body changes accompanying puberty, the ability of the mind to search one's own intentions and the intentions of others, the suddenly sharpened awareness of the roles society has offered for later life.Adolescents 'are confronted by the need to re-establish for themselves and to do this in the face of an often potentially hostile world'. This is often challenging since commitments are being asked for before particular identity roles have formed. At this point, one is in a state of 'identity confusion', but society normally makes allowances for youth to 'find themselves', and this state is called 'the moratorium':The problem of adolescence is one of role confusion—a reluctance to commit which may haunt a person into his mature years. Given the right conditions—and Erikson believes these are essentially having enough space and time, a psychosocial moratorium, when a person can freely experiment and explore—what may emerge is a firm sense of identity, an emotional and deep awareness of who they are.As in other stages, bio-psycho-social forces are at work. No matter how one has been raised, one's personal ideologies are now chosen for oneself. Often, this leads to conflict with adults over religious and political orientations. Another area where teenagers are deciding for themselves is their career choice, and often parents want to have a decisive say in that role.

If society is too insistent, the teenager will acquiesce to external wishes, effectively forcing him or her to ‘foreclose' on experimentation and, therefore, true self-discovery. Once someone settles on a worldview and vocation, will they be able to integrate this aspect of self-definition into a diverse society? According to Erikson, when an adolescent has balanced both perspectives of 'What have I got?' And 'What am I going to do with it?' They have established their identity:Dependent on this stage is the ego quality of fidelity—the ability to sustain loyalties freely pledged in spite of the inevitable contradictions and confusions of value systems.

(Italics in original)Given that the next stage (Intimacy) is often characterized by marriage, many are tempted to cap off the fifth stage at 20 years of age. However, these age ranges are actually quite fluid, especially for the achievement of identity, since it may take many years to become grounded, to identify the object of one's fidelity, to feel that one has 'come of age'. In the biographies and, Erikson determined that their crises ended at ages 25 and 30, respectively:Erikson does note that the time of Identity crisis for persons of genius is frequently prolonged. He further notes that in our industrial society, identity formation tends to be long, because it takes us so long to gain the skills needed for adulthood's tasks in our technological world. So we do not have an exact time span in which to find ourselves. It doesn't happen automatically at eighteen or at twenty-one.

A very approximate rule of thumb for our society would put the end somewhere in one's twenties. Love: intimacy vs. Isolation (early adulthood, 20–39 years). Existential Question: Can I Love?The Intimacy vs. Isolation conflict is emphasized around the age of 30.

At the start of this stage, identity vs. Role confusion is coming to an end, though it still lingers at the foundation of the stage (Erikson, 1950). Bubble witch 2 saga 2430. Young adults are still eager to blend their identities with friends. They want to fit in.Erikson believes we are sometimes isolated due to intimacy.

We are afraid of rejections such as being turned down or our partners breaking up with us. We are familiar with pain and to some of us rejection is so painful that our egos cannot bear it.

Erikson also argues that 'Intimacy has a counterpart: Distantiation: the readiness to isolate and if necessary, to destroy those forces and people whose essence seems dangerous to our own, and whose territory seems to encroach on the extent of one's intimate relations' (1950).Once people have established their identities, they are ready to make long-term commitments to others. They become capable of forming intimate, reciprocal relationships (e.g. Through close friendships or marriage) and willingly make the sacrifices and compromises that such relationships require. If people cannot form these intimate relationships—perhaps because of their own needs—a sense of isolation may result; arousing feelings of darkness and angst.Care: generativity vs. Stagnation (middle adulthood, 40–59 years). Existential Question: Can I Make My Life Count?is the concern of guiding the next generation.

Socially-valued work and disciplines are expressions of generativity.The adult stage of generativity has broad application to family, relationships, work, and society. 'Generativity, then is primarily the concern in establishing and guiding the next generation. The concept is meant to include. Productivity and creativity.' During middle age the primary developmental task is one of contributing to society and helping to guide future generations. When a person makes a contribution during this period, perhaps by raising a family or working toward the betterment of society, a sense of generativity—a sense of productivity and accomplishment—results.

Robert Mcg. Thomas Jr., 'Joan Erikson Is Dead at 95; Shaped Thought on Life Cycles,' New York Times obituary, August 8, 1997. Online at. ^ Crain, William (2011). Theories of Development: Concepts and Applications (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. Web.cortland.edu.

^ Macnow, Alexander Stone, ed. MCAT Behavioral Science Review. New York City: Kaplan Publishing.

P. 220. Human development: a psychological, biological, and sociological approach to the life span: 'III 5–8 (Play Age) Initiative vs. Guilt Family Purpose'. Human development: a psychological, biological, and sociological approach to the life span: 'IV 9–12 (School Age) Industry vs. Inferiority Neighborhood, School Competence '.

Human development: a psychological, biological, and sociological approach to the life span: 'V 13–19 (Adolescence) Identity vs. Identity Confusion Peer Groups Leadership Models Fidelity'.

Intergenerational Programs: Imperatives, Strategies, Impacts, Trends: 'First, he considers young adulthood (age 20–39) which he describes as the struggle of 'intamacy vs isolation.' '. Intergenerational Programs: Imperatives, Strategies, Impacts, Trends: 'In Middle adulthood (age 40–59), the conflict of 'generativity vs stagnation' arises'.

Intergenerational Programs: Imperatives, Strategies, Impacts, Trends: 'Finally, Erikson takes us to the eighth stage of adulthood known as 'later adulthood' (over 60) where development focuses on the integration of life's experiences, on embracing these experiences as inevitable aspects of oneself, and on accepting an orderliness in life and death'. ^. Archived from on 2012-11-27. Retrieved 2012-04-16. CS1 maint: archived copy as title.

^ Bee, Helen; Boyd, Denise (March 2009). The Developing Child (12th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson. Axia College Materials (2010). Child Development Institute. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

^ Allen, Eileen; Marotz, Lynn (2003). Developmental Profiles Pre-Birth Through Twelve (4th ed.). Albany, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning. ^ Gross, Francis L. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. P.

Wright, Jr, J. Eugene (1982). New York, NY: Seabury Press. P.

^ Stevens, Richard (1983). New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. Pp. Slater, Charles L. (2003), 'Generativity versus stagnation: An elaboration of erikson's adult stage of human development', Journal of Adult Development, 10 (1): 53–65,:.

Erik H. Erikson, Joan M.

Erikson, The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version (W. Norton, 1998). Erik H. Erikson, Joan M. Erikson, The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version (W. Norton, 1998), 4, 105. James Mooney, 'Erik Erikson' in Joe L.

Kincheloe, Raymond A. Horn, editors, The Praeger Handbook of Education and Psychology, Volume 1 (Praeger, 2007), 78. Erik H. Erikson, Joan M. Erikson, The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version (W. Norton, 1998), 106. Erik H.

Erikson, Joan M. Erikson, The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version (W. Norton, 1998), 106–107. Erik H. Erikson, Joan M. Erikson, The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version (W.

Norton, 1998), 107–108. Erik H. Erikson, Joan M. Erikson, The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version (W. Norton, 1998), 109.

Erik H. Erikson, Joan M. Erikson, The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version (W. Norton, 1998), 109–110. Erik H.

Erikson, Joan M. Erikson, The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version (W. Norton, 1998), 110–111. Erik H. Erikson, Joan M. Erikson, The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version (W.

Norton, 1998), 111–112. Erik H. Erikson, Joan M. Erikson, The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version (W.

Norton, 1998), 112–113. Erik H. Erikson, Joan M. Erikson, The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version (W. Norton, 1998), 112–113.

Wrightsman, Lawrence S. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. P. Erikson, Erik H. (1993) 1950.

New York, NY: W. Norton & Company.

P. Kail, Robert V. & Cavanaugh, John C. Human development: A life-span view (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA:.

P. 16. Gilligan, C. Harvard University Press. Erikson, Erik (1956). Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. Retrieved 2012-01-28. Marcia, James E.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 3: 551–558. Retrieved 2012-01-28.

Sacco, R.G. 'Re-envisaging the eight developmental stages of Erik Erikson: The Fibonacci Life-Chart Method (FLCM)'. Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology. 3 (1): 140–146.:. Yamagishi, M.

B., & Shimabukuro, A. 'Nucleotide Frequencies in Human Genome and Fibonacci Numbers'. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 70 (3): 643–653.:. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list. Perez, J.

'Codon populations in single-stranded whole human genome DNA are fractal and fine-tuned by the Golden Ratio 1.618'. Interdisciplinary Sciences: Computational Life Sciences. 2 (3): 228–240.Sources aboutErikson's stages of psychosocial development. Publications. Erikson, E. Childhood and society (1st ed.).

New York: Norton. Erikson, Erik H.

(1959) Identity and the Life Cycle. New York: International Universities Press. Erikson, Erik H. (1968) Identity, Youth and Crisis. New York: Norton.

Erikson, Erik H. (1997) The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version. Norton.

Sheehy, Gail (1976) Passages: Predictable Crises of Adult Life. Dutton. Stevens, Richard (1983) Erik Erikson: An Introduction. New York: St.